“Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy,

“Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy,

But not express’d in fancy; rich, not gaudy…”

The debate about the admissibility of burkinis on European beaches has mostly spared the American audience. But the issue is sufficiently grotesque to deserve a few related notes.

The idea that a state (French in the instance), can limit the freedom to wear clothing in the name of liberation is logically insane, historically ridiculous and politically idiotic. It is

“A fixed figure for the time of scorn

To point his slow unmoving finger at!” (1)

Some have rated the measure a sign of repressed white supremacy, hidden behind political correctness. More likely, it is a sign of the helpless, and therefore feeble reaction to the seemingly unstoppable biblical transhumance of peoples – in the name of globalization, annihilation of cultures, languages, traditions and massively promoted miscegenation.

Readers will no doubt remember that “the apparel oft proclaims the man (or the woman)“ (2), but the ban on burkinis is (was) designed as an instrument to infuse the taste of liberty and the awareness of the pleasures of (European) culture into Islamic ladies, reluctant to expose (what they rate to be) their own nudity.

I said that the ban “was” … because the French Council of State, before I began writing this, has deliberated that such a ban “gravely violates, in a clearly illegal way, the fundamental freedom of coming and going, and the individual freedom of creed.”

Nevertheless, the still-debated ban on burkinis rests on the idea that by showing rather than hiding her flesh, a woman displays conclusive and irreversible evidence of female liberation and gender equality.

If so, the legislators of the measure showed poor historical awareness – though it is known that distance, either of time or place, is sufficient to reconcile imaginative minds to inexistent facts and questionable conclusions.

The correlation between modesty in dress and female subordination is a relic of the extreme English Reformers who turned into Puritans, of the Restoration (after the French Revolution) and of the Victorian era.

The two-piece female bathing attire was already used in the imperial baths and spas of Rome. In fact, given the lack of any political weight of women in Roman and Greek culture, the reduction in volume of worn cloth was proportional to the reduction of their social and economic standing. By and by, Roman women did not much care “… to o’erstep the modesty of nature.” (3).

In fact, the French revolution was preceded by a popular rediscovery and return to Roman customs, attires and fashion. Men (and women) styled their hair “a’ la Brutus.” Women wore dresses with no pockets and practically no underwear. To enable ladies to carry with them some basic items, the French invented the hand-bag, called “reticule”, a word deriving from the Latin “reticulum” meaning ‘net.’ In fact the French “reticule” was anything but practical, hence the terms ‘ridicule’ and ‘reticule’ were used interchangeably, to mock the handbag accompanying the skimpy dresses.

But even long before, starting at the end of the 1600 and throughout the whole of the 1700, women’s breasts were practically uncovered.

But even long before, starting at the end of the 1600 and throughout the whole of the 1700, women’s breasts were practically uncovered.

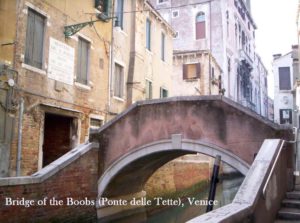

The unhurried tourist in Venice may venture to cross the “Ponte delle Tette” (Bridge of the Boobs), whose appellation and story are historically instructive.

The bridge is found in the sector of San Polo, which functioned, at the time of the story, as a red-light district. To lure customers, prostitutes used to lean topless, out of balconies or windows. Folkloric tradition attributes the habit to an ordnance issued by the Venetian Republic. The reasoning being that the sight of topless women would promote heterosexual excitement in male viewers, and thus help stem the increase in homosexuality affecting the city.

That sodomy was a problem is attested in the extended and massive Chronicles of Venice written in Latin by one of her citizens, Marin Sanudo, (1466-1536). In which we read,

That sodomy was a problem is attested in the extended and massive Chronicles of Venice written in Latin by one of her citizens, Marin Sanudo, (1466-1536). In which we read,

“In order to eradicate the abominable vice of sodomy (abhominabile vitium sodomie), two noblemen per sector will be selected. And every Friday they will interview medical doctors and barbers (note that until historically recently, barbers were also surgeons and surgeons were barbers). If any doctor or barber, during the week, has been called to cure colo-rectal ailments in men (or women) deriving from sodomy, (in partem posteriorem confractam per sodomiam), they are obliged to denounce the fact to the authorities. Following the indictment, the sodomites will be hanged between two columns in a square (Piazzetta) and burned until they are reduced to ashes.”

One such punishment was inflicted on Bernardino Correr who, in 1482

“… attempted to carry out acts of sodomy on Mr. Hieronimo Urban, a most handsome young man, during one evening when Correr found Urban in the pathway leading from Ca’ Trevixan to S. Bartolomio. To this deplorable purpose Correr cut the suspenders of Urban’s stockings. But Urban did not want any of this and denounced Correr to the Council of Ten.”

Throughout the 1600 and 1700, low neck-lines approaching toplessness, were common, along with enormous shirts ending in wasp-like waits and breasts purposely augmented and raised via busts and corsets. We can detect in the vestment a different interpretation of the female body.

For men, in turn, it was the time of the Renaissance tights, remarkably similar to the now fashionable nylons, worn by ladies.

And long before, Dante Alighieri, the Shakespeare of Italy, (1260-1321), upbraids the women of Florence, for their most visible breasts, “…le sfacciate donne fiorentine l’andar mostrando con le poppe il petto” – the shameless Florentine women who go around showing their breast with their boobs.

But I digress. Actually, the quickened evolution of clothing styles is coeval with the birth of capitalism, in the 13th and 14th centuries. That’s when fashion, as we know it, was born. The word ‘fashion’ derives from the old French ‘façon’, meaning appearance, pattern, design, etc.

From the mid-1200 onward, fashion was linked to a rapid change in the shape and color of dresses. At first, fashion was the monopoly of the upper-classes, but gradually it Reaganesquely trickled down, at least, among the ancient equivalent of today’s urbanized middle classes.

Coeval with the explosion of fashion is the birth of sumptuary laws throughout Europe, aimed at forbidding the ostentation of luxury. In women primarily, but not only,

“… for it is not vain-glory for a man and his glass to confer in his own chamber.” (4)

In fact, ample literature (and paintings), prove that fashion affected both men and women. For example, in evaluating the attire of an English suitor, a Venetian lady says,

“How oddly he is suited! I think he bought his doublet in Italy, his round hose in France, his bonnet in Germany, and his behavior everywhere” (5)

Case history, in the enforcement of dress codes and sumptuary laws, has a connection with the burkini issue, though from a different angle. In 1278, after Bologna became part of the Papal state, sumptuary laws forbade ribbons and long trains of dresses, and imposed the use of a veil on women when in church. This caused frequent brawls between the people and the papal controllers.

Throughout the Venetian Republic sumptuary laws prohibited women from “hiding themselves under expensive and luxurious dresses.” In the city of Verona, the thus-repressed ladies commissioned local graffiti-artists to write on the walls “F…k the cuckholds who don’t see what goes on at home.” (bechi fotui no vedè quelo che gavè in casa). The inference being that the concern about verecund modesty displayed in church clashed with the morally-lax general way of living, hence making the sumptuary laws silly and hypocritical.

However, a more practical objective, besides the enforcement of modesty, was to restrain and reduce the outward display of class differences. History printed in official school books teaches us that class struggle was a 19th century phenomenon and a Russian syndrome. In reality, throughout the history of capitalism rebellions were bloody, fierce and frequent. For, while a small privileged elite lived in luxury, the coffers of the majority would “sound with hollow poverty and emptiness” (6)

But there were also practical reasons for discouraging elaborate and long dresses with trails. St. Bernardine from Siena warned from the pulpit,

“O ladies, tell me: what happens to her trail when a woman walks along the street? It raises dust, and in the winter it is soiled with mud. He who follows her breathes the incense she produces, which is rightly called the incense of the devil.”

Nor an elaborate dress, jewelry and make-up necessarily enhanced the sex appeal of the wearer. Latin writers were explicit in their criticism of gaudy and ostentatious dresses and ornaments. Ovid warns,

“… but you (women) don’t load your ears with the precious stones that an Indian negro gathers in green waters; nor show yourselves laden with gold-embroidered gowns. For your luxury cancels the appeal with which you would conquer us.”

Lambasting both fancy dresses and applied cosmetics, St. Ambrose says that women,

“From the adultery of the face they proceed to meditate on the adultery of their chastity.” A point on which Ambrose and Mohammed would have agreed.

Given the actual history then, the act of not disrobing at the beach seems almost an indirect act of compensation against female submission. Or rather, there is a clear link between fashion, bikinis and capitalism. Capitalism rates traditional attire and costumes as obstacles to marketing, for tradition implies lack of change and durability, antithetic to fashion, which is but market-induced obsolescence, promoted as a spontaneous change in taste.

And market is such a powerful force that,

“New customs,

Though they be ever so ridiculous,

Nay, let them be unmanly, yet they are followed.” (7)

In the end, removing a veil from Islamic women and a cover from their legs, hardly suggests female emancipation. Rather, it implies a submission to the market, a word that, in turn, implies male domination. For the market, especially in Western neoliberal society, is the quintessential user and exploiter of the female body. And legislators ought to distinguish what is established because it is right, from that which is right because it is established.

Personally,

“Old fashions please me best: I am not so nice,

To change true rules for odd inventions.” (8)

but, after this curious and politically induced interest in attires, I am tempted to change my mind and examine more carefully my outward appearance. Maybe I’ll follow the example of Richard III,

“I’ll be at charges for a looking glass

And entertain a score or two of tailors

To study fashions to adorn my body.

Since I am crept in favour with myself,

I will maintain it with a little cost.” (9)

** 1. Othello

** 2. 3. Hamlet

** 4. Cymbeline

** 5. Merchant of Venice

** 6. King Henry IV, p.2

** 7. King Henry VIII

** 8. Taming of the Shrew

** 9. King Richard III

In the play (opening quote). Polonius gives his son Laertes a set of precepts to follow while in Paris.

Would you like to have immediate access to the most appropriate Shakespearean quote, for your speech, presentation, essay, report or book? Consider using the Reasoned Dictionary of Shakespearean situations. “Your Daily Shakespeare, an Arsenal of Verbal Weapons to Drive your Friends into Action and your Enemies into Despair” – is the most useful, unusual and unique Shakespearean Dictionary ever printed. Over 1400 pages with an Analytical Index of over 10,300 cross-correlated entries. Now on Kindle, $5.95.